Spring Awakening

Something about spring makes me feel alive! Perhaps it’s because I was born on the first day of the season. It always gives me the feeling of a new beginning.

- Mar.2022

Teen Vogue Executive Editor Danielle Kwateng and artist Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe are part of a new generation of Ghanaian creatives bringing their vision to the American cultural landscape.

One of the hottest young artists of the moment, Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe and Teen Vogue’s Executive Editor Danielle Kwateng sat down with Ngaire Blankenberg, the new Director of the Smithsonian National Museum of African art for a spirited conversation for Luxeicon. Thanks to tech, borders were erased and the intimate conversation took place across three time zones – Washington, DC, Portland and Accra- three completely different centers of consciousness.

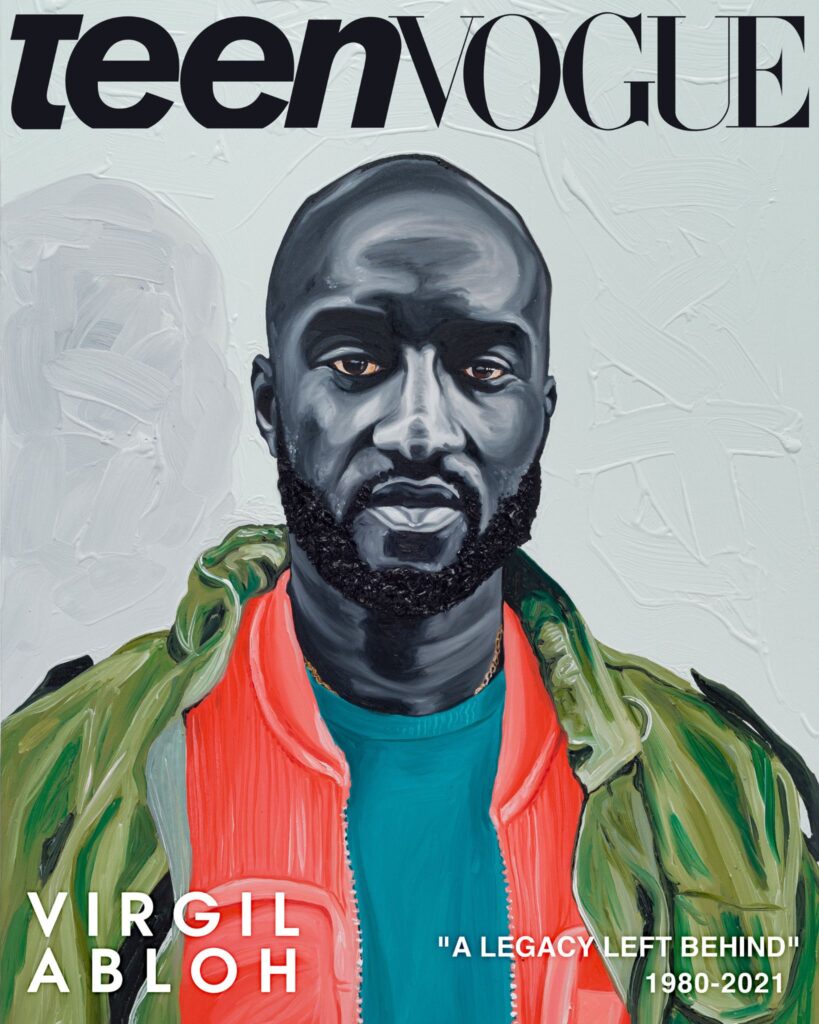

While Kwateng and Quaicoe have never met in person, the two recently collaborated on an iconic piece of, and for, the culture—the special edition cover of Teen Vogue celebrating the life and expansive impact of creative visionary, Virgil Abloh.

Here, the trio’s in-depth conversation touches on everything from living in two worlds to how creatives can ensure their work is regenerative for the next generation.

Ngaire Blankenberg: There’s an interesting conversation around young people owning their voice and recognizing that it’s something to be owned. What do you see your role in that process with Teen Vogue magazine?

Danielle Kwateng: I’m in a really blessed position because I know both worlds. We always talk about a double consciousness, and I think I have a triple consciousness as a Ghanaian American. I know white American culture well. I know Ghanaian African culture well and I know Black American culture well. I’m in it with all three and I can see something in white culture that was taken from Africans. I can see something in Black culture that was derived from Africans. I can see things in African culture that was derived from Black Americans, so I’m in a unique position because I can see it all and I can make sure that the most accurate and intentional and respectful stories are being told by the right people.

“When I say that, I mean another big thing of mine–it started really at Vice–I noticed a lot of, I call it ‘ghetto tourism,’ where they put white people in our spaces and they tell a story that feels kind of National Geographic-y. You put a white guy in Compton to talk to Kendrick about hip-hop in southern LA and it feels very voyeuristic. I’m in a unique position to say, ‘Hey, there are Black writers from Compton who can tell this story … from a respectful, authentic lens that isn’t riddled in being a culture leach, a culture vulture. I think that’s something I’m super mindful of with everything we do at Teen Vogue to make sure that the right people are telling the story.

For instance, the Virgil cover. I said, ‘We absolutely have to have a Ghanaian artist do this portrait. And we also need to have a Ghanaian or a Black American writer writing the story. And here are the voices that we need to have in the story as well because [Abloh] had such a huge impact on the entire fashion community, but specifically for black and brown creatives and artists.’ There’s a story there of being a single black person in a very white elitist space and there’s a story there that needs to be told from the right voice. That’s the position I’m in, to make sure that’s what’s happening and I’m not just willy nilly giving the stories to anybody. Let’s tell whatever stories, let’s pick whoever is hot. No, what’s the origin of the story, and what should be discussed?

Blankenberg: Let’s go to you Otis on that. How did you feel about doing the painting? What do you think you brought to the painting that perhaps someone else couldn’t have?

Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe: Well, I may not know about the other artists, but how I saw it when Teen Vogue first approached me and spoke about it, I went back to find out what are the other stories behind that and who is writing this. It felt right to me in the sense that as a Ghanaian, we were inspired by him and his work, and like Dani said, if we are to tell this story through painting, it should be from my sight and how I saw him. Even though the picture was not taken by me, I still have to paint it in the sense that, ‘This is what I feel, this is how I see him.’ Hopefully I can translate that … to ‘this is our person, this is what he meant to us.’ Even though it’s just a still photo, I still have to be able to capture those emotions, everything that I felt when I first heard the news of his passing … but it just felt right.

Blankenberg: How do you know when something feels right? I think it’s interesting talking about intention and authentic voice.

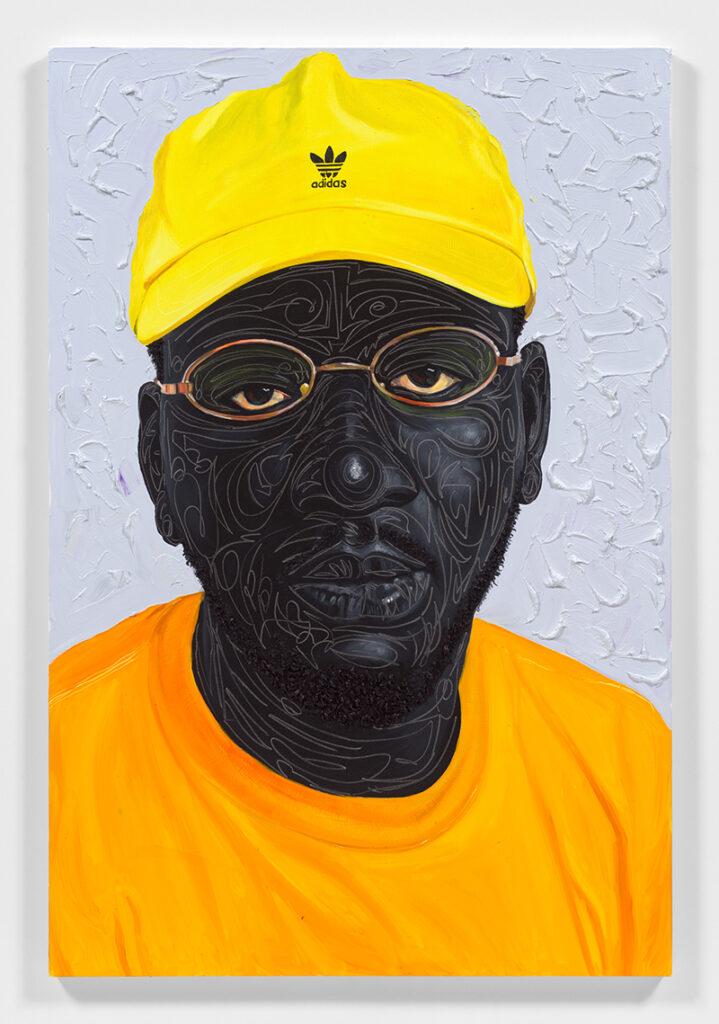

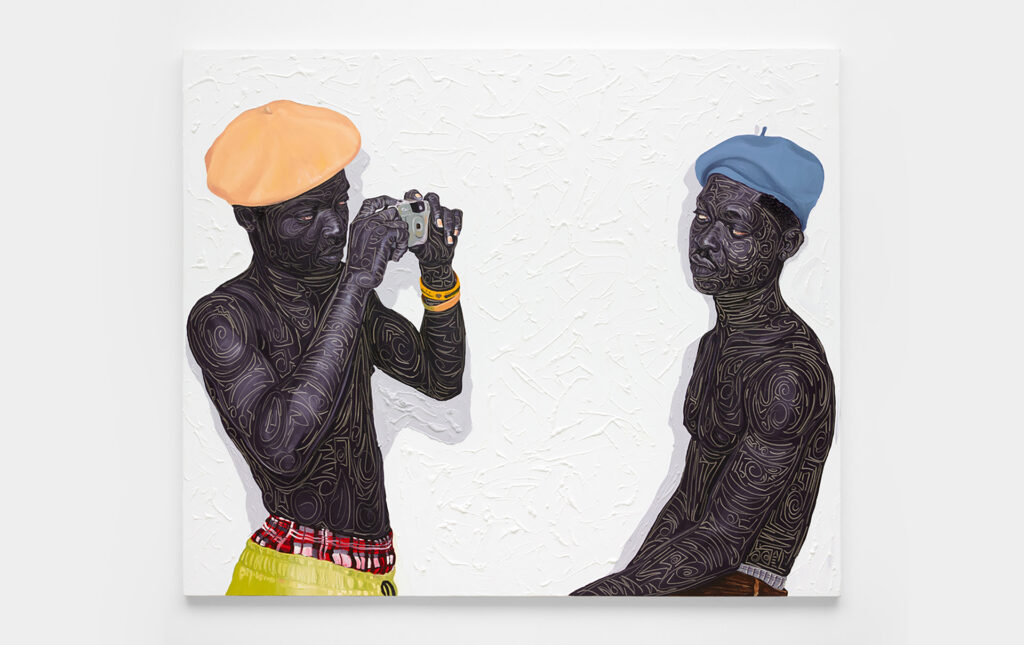

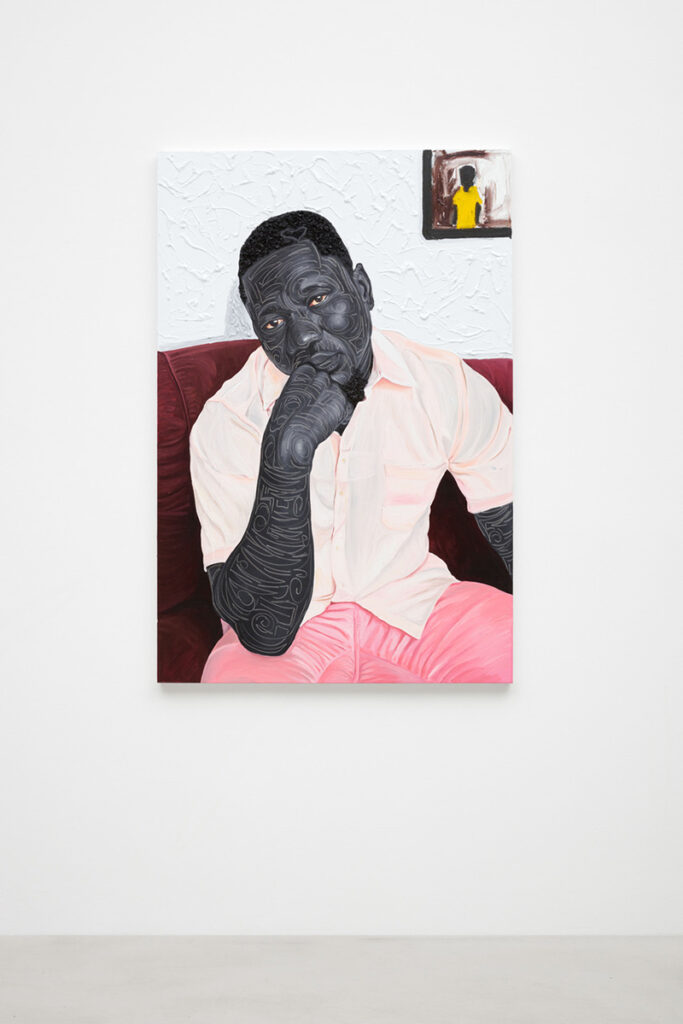

Quaicoe: It’s a feeling you can’t really explain. It’s just something like an instinct. It’s the same way when I’m painting my subjects. I’m very picky in choosing who I paint because if I’m painting somebody, it doesn’t represent just the person, but it represents a group of people. It’s talking about people’s background, so you have to carefully choose subjects that represent the rest of the people. It’s always on instinct and sometimes I look at features because I also talk about my people, my culture, and how we look. When I came to the States people didn’t really learn if I was an African American or African unless they heard me speak or saw how I dressed, and there are certain features [of my culture] so all these things are very important for representing my people. But most of the time it’s on instinct, you feel this person would be right as an icon for the subject.

Blankenberg: I love the way you’re connecting to not just one person but perhaps the group that he is part of or the community that he is part of. Do you see yourselves, Dani and Otis, as being part of the same community?

Quaicoe: Definitely. I mean, there are things I didn’t know when I was living back in Ghana. We only see what’s on the news, but we don’t actually experience it. Back home, all that we know is just limited, but there is more to the story, so once you get here you feel like—as an artist—you become sort of like a journalist. You are here and you are experiencing what’s going on around you, learning about history that we only read in books and there is more to what we read, so it’s kind of like you become the voice, the channel, sending messages back home, educating them. This is what’s really happening, this is what’s really going on.

Blankenberg: I’m so interested by that. The artist as journalist. Because Dani you were almost talking about the culturist also as a politician or bridging that gap between culture and its relevance in the world. And, I wonder how each of you see the role of culture and art respectively.

Kwateng: Art is literally a snapshot of what’s going on in the world, whether it’s politically, scientifically, it’s the best way to gauge how people feel and what they’re thinking and what they’re going through at that moment. Art and pop culture to me are a nebulous concept. Art is music. Art is painting. Art is photography, and so I think there’s no better way to know what that moment in time was than to look at the art. There were so many art collectives in the ’60s and ’70s that were making political art around different movements, whether it was the Vietnam War or whatever the issues of the day were. Even the music was about political unrest in the country. It was about that very specific moment in time. The same thing fast forward to now. The books that are being written, the music that is being made, the art that’s being produced is very keenly specific to the things that were going through as a global society. I think they’re one in the same in terms of art and culture, and I think they are merely reflections of what’s going on in the world. I think they’re the best mirror of what’s happening.

Blankenberg: I obviously agree and I’m pretty sure Otis agrees, but I don’t think everyone necessarily agrees because there isn’t a huge following around visual arts, for example. I wonder what the reaction was to putting not just Otis’ painting, but putting a painting on the cover of Teen Vogue, what was the reaction to doing that?

Kwateng: One, I know there’s so many amazing Ghanaian paintings including Otis’ whose work I’ve been a fan of for a little bit now, and so I wanted a way to depict Virgil in a very respectful way that wasn’t just an old photo. I wanted it to be a rendering of him because I felt like, yes we could get photos of people he influenced or a shot of an Off White runway, but it felt like it needed to be him, and it needed to be him in a way that I think Otis did phenomenally that felt stoic and intimate and respectful. I think that even the colors used, the dark blues and blacks, the strokes of his skin, there’s sadness in that. But it’s also hopeful, the pops of color in his outfit and the surrounding landscape that is behind him. I feel like we achieved it. I feel like it was the best way to pay homage to him other than just a regular photo that wouldn’t do it justice. I loved it.

Quaicoe: I was so honored when [Teen Vogue contacted me] … I never thought I’d do something so iconic, especially something that’s so meaningful to everybody back home. I’m so truly honored you saw that in me and that you chose me to do it. And then also the color, I chose those bright colors because it’s in the form of celebrating his life, the joy he brought to people, his people, even to the rest of the world. And also, like you said, the subtle emotions, trying to remember that aspect of him … just to show who he was. He lived a beautiful life.

Blankenberg: How did you feel about your work’s primary exhibition platform being in a teen fashion magazine, because I imagine that’s different for you than being in a gallery.

Quaicoe: It is different in the sense that the focus behind it or when we were doing an exhibition in a gallery we’re talking about an issue that is really going on, but with the Teen Vogue cover we’re talking about an individual who is representing a group of people, so it is important to capture the person’s essence that will also translate to the viewer. When the viewer sees it, he or she will also feel that emotion. It is always different when you’re painting an individual that represents a whole group of people.

Blankenberg: I wonder if you guys think that your own identities play into your abilities to be extremely fluid in how or where you do your art?

Quaicoe: I put myself in every bit of a subject. Most of the time I paint people of color just because of the experience I got when I first moved to the States. Like I said, we watch the news, we hear about racism and all the rest of it, but you don’t really because you’ve not experienced it. Sometimes you watch it [on the news] and in a few days you forget about it, but when I moved here and I started experiencing that myself. People were calling me names. I’ve had moments where teenagers would drive by and stop and make monkey faces. For me, in a sense, I wasn’t offended because everything was new to me. In my country, we are all Black so when someone calls you the n-word you don’t really take offense to it, until you move here and you start to make friends with African Americans and you hear it. Then you start to feel it more, and then also when you start to experience it, everything starts making sense—why the struggle is going on, why people are protesting.

I make sure I put that in my subjects because I see myself in them, the same things happen to me. If I’m telling a story, I tell it from their side and my side and put those two together. I always tell people, I’m here now in the States, I’m not identifying as African, we are identifying as Black people, African American. Until we start to have a conversation, when someone is approaching me, talking to me, not as an African but as a Black person, it’s like we are all one people. As I’m telling the story, I’m telling it from both sides, their side, my side.

Blankenberg: What was it like going the other direction Dani? You grew up in a Ghanaian home in America, but now you’ve gone back to Accra.

Kwateng: It was a wild ride. It’s still a wild ride. Otis knows, I’m sure. Here’s the thing, some people will tell you, ‘Ghana! I’m going to go back home,’ and they make it seem like this Eat Pray Love moment. Sometimes it feels like that, but the truth of the matter is Ghana, Accra, is a developing city, nation, and they have some of the same issues we have [in America] but at the end of the day it’s us. There’s a sense of safety and peace that I have here that I do not feel when I’m in the States. There’s a sense of belonging that I don’t feel always in the States. Otis was talking about coming to the States and people making fun of him and being ridiculous. That’s not something that happens here in my North Legon neighborhood. If anything, they say I talk too fast and I need to work on my Twi. It’s not the same level of oppression, it’s not the same cloud, but yes, could the roads be better? Yes, it’s a mix of day to day things.

The thing is: Anybody who tells you moving here is an absolute dream is a lie. The lights go out, the road aren’t great sometimes, the traffic in Accra is the worst it’s ever been, but it’s Ghana, so it is what it is. You take it because it’s your people and we’re going to be okay, and there’s a sense of community and care here that you just will not ever feel as a Black person in the States. It’s just not the same. I don’t feel scared when I go out at night around the corner to get something really quickly the same way I do in Brooklyn sometimes. I don’t ever feel like I’m going to be, God forbid, in a shopping mall or if I have kids and they’re in school that somebody’s going to shoot them randomly. It’s just not something that happens here. It’s just a totally different cultural perspective experience.

Is it a dream everyday? No, but it’s been an incredible deep-dive learning lesson into my comfort level, my strengths, my understanding of how complex and different Ghanaians are. We’re not monolithic in any way. Otis, I’m sure you know, I was in Busua Beach this weekend, outside of Takoradi, and I was hanging out with a whole bunch of Ghanaian surfers. A couple weeks ago, I was with some Ghanaian skaters. There are art critics, there are cooks, everybody has their own sense of identity within the Ghanian gaze. It’s not monolithic at all in experience or people. You just have to be open and I think that’s the biggest thing: I’ve learned to just open my mind about what it is to be Ghanaian, and when I come back to the States, I look at things so much differently.

Blankenberg: Otis, what do you love about America?

Quaicoe: First of all, it’s the resources … to be able to develop your skills. Back home I think we only have one art shop that sells art materials so people have to travel all the way from the other regions. When that happens, it’s really difficult for people to continue with their practice. And also, the culture … like Dani said, it’s just so different from the way we look at things back home.

Blankenberg: I’m curious what you both see as different and the same in young people … Gen Z and Millennials, which is very much Dani’s target market with Teen Vogue, and how it’s a generation that’s being erased and marginalized a lot and having to learn to speak their voice. I wonder if it’s the same thing in Ghana. The demographics are very different. There’s more young people in Ghana as a percentage of the population than there are in America. But I wonder within the attitudes, the aspirations, the behaviors, what are the things that are similar and what are the things you see are different?

Kwateng: When we were talking about Virgil, there were two points that I wanted to make which answer this question as well. The two things that made him so dynamic more than any other designer of his time was that, one, he was really invested in youth culture. He was really attuned to what young people were thinking, interested in, hate/love, everything, even the skate park [in Ghana] he invested in. He put his money behind, and really believed in, young people saving the world. Number two was he called himself a maker. This is somebody who was a designer, but he designed a plane, he designed a bottle of water, he went to school for architecture. When we talk about Ghanaian youth, I think Virgil’s actually—even though he was raised in Chicago—he’s a really great example of Ghanian young people because, one, they’re interested in each other, they’re interested in community and investing in each other, and two, they are a jack of all trades. Young people are no longer like, ‘I will be this one thing and this is the only job I’ll have forever.’

They’re open to being creatives in the most open expansive sense of that world, same with Otis. He usually does large canvas paintings that are in exhibits, but a magazine asked him to make a cover and he retrofitted his skills to do that. It’s just indicative of young people here, where they are willing to figure it out to use whatever channel it is to express themselves and they’re interested in bringing their friends on board, too, to share the experience, and also to just build build build as much as possible.

Blankenberg: There’s two things that I’ve been thinking a lot about in my work. I would like us, as a museum, to be part of the ‘regenerative’ art ecosystem. I think we’ve existed for a long time in a very extractive environment where you take without attributing, or you take to own, to perhaps exhibit without necessarily giving something back, without ensuring that’s a regenerative process that’s going on. I wonder how each of you seek to foster that regeneration, and I wonder if you think that’s important?

Quaicoe: Most of my inspiration comes from the medium. You take and then you give back. And also, whatever I’m doing now, I always think about the next 10 or 15 years. What I’m doing now is documentation for the next generation to go see later and say, ‘Oh, this is what we were talking about during this time.’ It’s kind of like a regeneration. Just like how I go to the museums today, [those artists] were documenting things when they were alive during that time and I have been able to pick up and learn from them. I’m playing my part as an artist.

Kwateng: I was thinking about last year, when I was part of a collective, See in Black, which was a photography collective with Joshua Kissi, Micaiah Carter, Andre Wagner, and we essentially wanted to figure out a way to raise money for the Black community during the George Floyd and Breonna Taylor protests. We asked a whole bunch of Black photographers to submit a single photo and then we worked with a printing company to print the photos and sold them, and all the proceeds we gave to five different organizations. It was a way to literally reinvest what we’d been given, the medium to tell our stories from. We saw a lot of photos being taken of protests and our likeness that was being used for media consumption, but there wasn’t a lot of conversation about investing in and ways to dismantle white oppression and systematic racism. Our thought was, ‘Let’s go to our circle of our young photographer pool of people and the photos that they’ve taken—or I should say made because ‘taken’ is one of those Colonialism words which is a whole other conversation—the photos that they made, and reinvest them in the same communities that they made the photos of.

I think that’s pretty much what all young people are trying to do at this point … for too long people have made money off of our likeness. How do we give back to the places that we took from? It’s something that I’m excited to do but I think a lot of us in this current time and hopefully going forward are really interested in that reinvestment as well.

Blankenberg: How do you think that reinvestment works within the broader community? How do you see this new community that is much more international but also much more intensely local, and how do they feed each other?

Kwateng: There’s such a huge conversation to be had about the internet and how it’s totally changed everything. Mainly the accessibility to information and sharing is huge. We would be fools to be a publication called Teen Vogue if we were solely focused on the U.S. Because teens, young people, are not only concerned with what’s happening locally. You can’t be. Global warming is a global conversation, the weather feeling different outside, the food being unclean, and access to healthcare are global conversations. We can’t have tunnel vision when we report on these things. Living in Ghana and still being connected to this very Western publication only helps the story telling, only helps the perspectives, only helps introduce color to the stories we’re trying to tell and it only makes us better and stronger, and more relevant.

Blankenberg: You spoke about something similar Otis, but it’s almost a very different way. I noticed how you talked about empathy when painting Virgil. The universality perhaps was in the emotion, the feeling, the intimacy of it, more than almost this global idea, so I do wonder how you bridge these massive geographic gaps or whether you even see them as gaps when you have a subject who may be similar or different to yourself.

Quaicoe: When I started off as an artist, I was going to art college, I was taking a class in abstracts. I love abstract because it was the only way I could express myself. Knowing kids from Africa, we really are brought up in a way as a kid you can’t always express yourself how a Western kid can express themselves. We were taught how to respect your elders and how to talk a certain way in public, so the only way I could explore and express myself was through colors and abstract. When I started taking lessons in photography, then I started with portraits, taking pictures of people, I started learning about people and other things they do, who they are as individuals. But back in art school, the perception was given that you have to paint the African continent, the African women carrying baskets and kids on their backs. When you go on the internet this is what you see. For me, traveling [to the U.S.] and finding there are whole other stories you can talk about. That is what my focus became … and that message was also sent back home for emerging artists to see and breaking that cycle of limitation of only painting [stereotypical] African women, but instead using themselves, figuration, of other people to tell other stories like global warming, racism.

Blankenberg: I think it’s so interesting because the way that you speak, this trend in figuration and painting and in photography, about the need to represent the Black figure and the moment we’re having, I think is extremely powerful and amazing but I also think it’s very American. It’s very shaped by an American and an individual need for presence, and it speaks very much to a visual language and an articulation that is much more American than it is African. I find it very interesting the way that you speak to perhaps the notion of one person as a stand-in for a community and the notion of bringing abstraction, which is a very different way of looking at the figure, even though the result has a similar language. That is obviously the magic that you bring to it because you bring to it a very Ghanaian way of approaching your subjects.

Quaicoe: And again it all comes back to the experiences I’ve had here because most of the time when people get to hear my accent they’re like, ‘Oh, where do you come from?’ And I say Ghana, and it’s because they don’t have knowledge about it, that’s why they ask, ‘Oh, do you live with the lions? Do you sleep on mats? What do you wear? Do you guys have cell phones?’ We have skyscrapers like they do in the U.S. We drive fancy cars, we have computers and all that. That’s why I also focus on fashion when I’m dressing my subjects, all colorful, wear these Nikes. It’s part of informing people here [in the U.S.] that, ‘Hey, we are all about this life too,’ It’s not just poverty, suffering. It’s a way of life, sending messages back and forth, mating the two cultures together, the way we look, features, the way we dress, our hairstyles. Because we all know if you go back in history how [with] slavery … we are all connected. So there is a difference, but not much.