Finding Balance

As we head into a summer of in-person events, I’m in search of that elusive goal of having it all.

- May.2022

Dario Calmese refers to himself as a “generally curious fellow,” so it’s no surprise that his work, which spans across various genres, continues to have an indelible impact on the world of art and fashion. In showing up as himself, a Black, queer man from St. Louis, Missouri, he’s been able to disrupt spaces that weren’t designed with him in mind and spark conversations that are long overdue. His work for one of the biggest nights in fashion, The Met Gala, is just one example of how he’s managed to integrate art, fashion, and beauty with history.

This year’s theme, “In America: An Anthology of Fashion,” is based on part-two of an exhibit from the New York City museum’s Costume Institute. For the exhibit, nine directors staged the Met’s period rooms to align with the theme, and Calmese captured images of these rooms. “The Met asked me to come in and interpret the rooms in my own way, photographically,” said Calmese. “I went through all of the costumes and rooms, and did a series of images. One of them is the main image that advertises the exhibition, which was done in the Rococo room.”

In taking on this assignment, he sought to answer the question, “How do we use fashion and interior design to speak to this larger history of America?” Calmese’s work is in constant conversation with the concept of design. Specifically, his understanding that we’re all living in preexisting designs that, for many of us, were not created with us in mind. For him, in photographing these curated spaces in a way that would speak to our larger history, it was about the unveiling of hidden stories.

“In that one key image, it is this woman decked out in this extremely opulent gown in this extremely opulent space, and she’s looking in the mirror. And that mirror reflects a very dark image,” said Calmese. “This is really about the history of America and what America has to face with itself in order to move forward. It’s this juxtaposition of elegance and luxury mixed with this look at a dark past. And in that regard, I removed, imposed all of the other elements in the room so as to not to distract. So that we had a focus point.”

This isn’t the first time Calmese used art to create space for conversations about our history and its impact on our present. This is something he is known for.

In July 2020, Calmese made history as the first Black photographer to shoot a Vanity Fair cover. That cover, featuring Viola Davis—skin draped in blue, back to the camera, and gravity-defying hair—was a love letter to Black women, and a bold statement in the midst of a global movement for Black lives. From his use of the color blue, to the positioning of Davis’s body, there was an extensive amount of research conducted in the planning of the shoot.

Regardless of where he is or what space he’s occupying, Calmese says it’s important for him to always speak truth to power. “My spirit just can’t rest if I don’t say something, if I don’t bring something up, and do it from a place of compassion and wanting to get to a level of mutual understanding,” says Calmese. “That’s what I’m always after—what’s not being said. Not just consciously, but what’s not being said due to your inability to even see? Those are the things that I’m very much interested in.”

Calmese has been mindful of what isn’t being said since his formative years in St. Louis. As the son of a father who’s a minister and a mother who’s a seamstress, he found inspiration in the Black church—from its theatricality and fashion to the mystery of God. But he didn’t see himself—a Black, queer, burgeoning creative—reflected in that space, or the other spaces he grew up in. “Most of my life has been in the pursuit of myself and my tribe. And much of my work has been about, not only reflecting Black beauty and elegance but also the multiplicity of Black life. Because coming from the Midwest, in a very traditional, typical American household and environment, you really did not see that multiplicity of Blackness and the Black experience.”

In the pursuit of self, Calmese crossed paths with Geoffrey Holder, whose friendship and mentorship had a profound impact on him. Holder was another multi-talented artist, having been the first Black person to win a Tony. He was awarded for Best Director for The Wiz on Broadway (for which he won another Tony for his work as costume designer). Holder was a singer, dancer, actor, painter, sculptor, and director. To sum it up, like Calmese, he was a storyteller.

“With Geoffrey, I found that person. That mentor who was moving through the world in that multitudinous, multivalent dynamic way that I was. Geoffrey, in a way, gave me permission to be that person and to walk in that way.” Calmese spoke of how Holder showed him he wasn’t limited to one thing. Following the passing of Holder in 2014, the lessons continued. Calmese inherited 2,000 books from Holder, and that was the launching pad for The Institute of Black Imagination—“a tribe of mentors, from the pool of Black genius.”

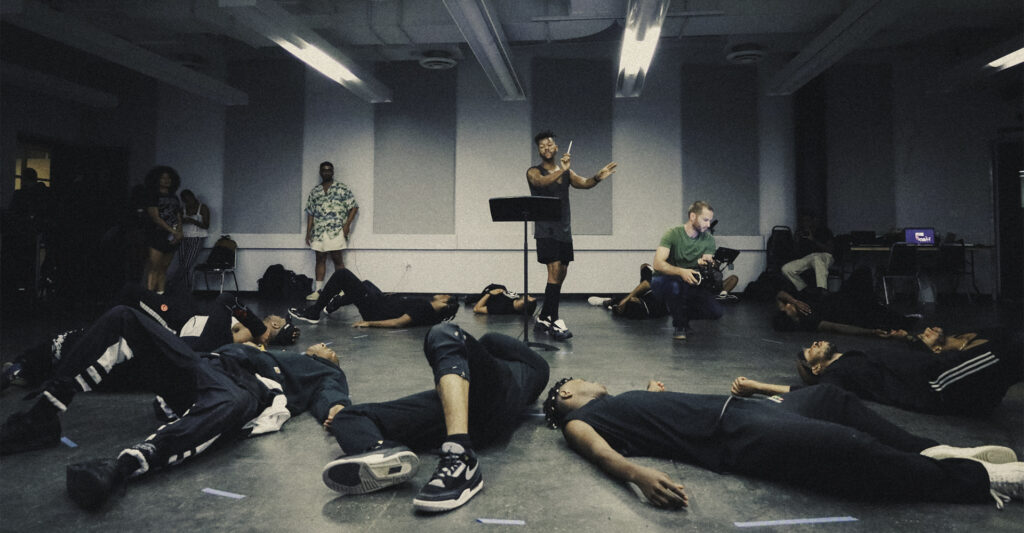

“I realized Geoffrey had left behind this roadmap, this blueprint, to creativity. I thought other Black and brown individuals need access to the information. I didn’t want things to just be scattered to the wind after he passed.” The Institute of Black Imagination started as an archive, filled with resources, but has grown, and continues to grow into a space for Black creatives to explore, connect, and find inspiration. Right now, it’s a digital space and podcast, where conversations on radical imagination are being held, but it will soon become a physical, pop-up space in New York City. “What does it mean to bring Black imagination into space and time? So people can touch, feel, and experience it,” says Calmese. “When you walk in, you’re going to be met with Black design and Black thought. It will shift this idea of Blackness as performance on an understanding that we are producing, creating, and designing what the future will look like.”

Black imagination, like Calmese’s work—such as his photographs for the MET and those history-making images of Viola Davis and his partnerships with design powerhouses like Pyer Moss and even Adobe—it’s all a testament to the role that Black artists play in designing our realities. “Not only are we reliant on Black imagination to help us reimagine what is possible for us,” he said, “ it can bring about a new way of existing in the world that liberates many people.”